ARGUMENTATION

(Toulmin,)

(Toulmin,)

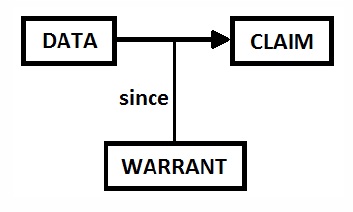

Scientific arguments can vary in complexity. Depending on the structure, the argument will look (and sound!) different. For example, here are two examples from Toulmin’s model of argumentation.

Parts

Parts

- Claim: a conclusion or assertion. (A counter-claim is an opposing conclusion or assertion).

- Data: the evidence and facts used to support the claim.

- Warrants: statements (rules, principles, etc.) which explain the connections between the data and the claim/conclusion/assertion.

This model represents a relatively simple concept of an argument. By working within this model, students are encouraged to question whether a claim has any merit by considering the evidence, principles and assumptions on which the claim is based.

Here is an example which puts this model into practice.

Chelsea is a better football team than Arsenal [claim]. It has won more football matches at home and away [data] because its players have superior skills [warrant].

(Osborne, Erduran and Simon, 2004b)

A claim is presented, which is then supported through raw data and a sentence applying that data to the claim.

Feedback on the IDEAS project (IDEAS 2004) suggested that students can struggle with the difference between data and warrant, so it can be simpler to consider these together and think of them as justification.

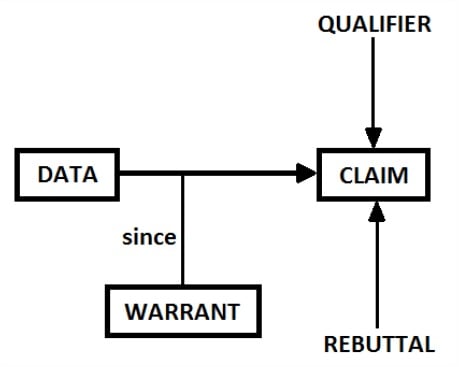

This more complex model also includes qualifiers and rebuttals.

- Qualifiers: conditions under which the claim is true

- Rebuttals: statements which contradict the data or warrant

Here is a student example which has put this model in practice.

Seeing because light enters the eye makes more sense [claim]. We can’t see when there is no light at all [data]. If something was coming out of our eyes, we should always be able to see even in the pitch dark [rebuttal]. Sunglasses stop something coming in, not something going out [data]. The only reason you have to look towards something to see it is because you need to catch the light coming from that direction [rebuttal]. The eye is rather like a camera with a light-sensitive coating at the back, which picks up light coming in, not something going out [warrant].

(Osborne, Erduran and Simon, 2004b)

This argument, compared to the simple model, is multi-layered; using more than one piece of data and a rebuttal to extend their argument further.

Counter-argument is another term used in these resources. It is an argument (consisting of data and a warrant) for a counter-claim.

As students become more familiar with the skills required in argumentation it is expected that their arguments will increase in both their complexity and quality. A breakdown of different levels of argument is outlined below:

- In its simplest form, an argument must consist of a claim and at least one reason for accepting the claim. The nature of the justification will depend on the type of claim. In this context it will be expected that data from practical work or theory statements provided will be used as justification for the claim.

- As students' skills increase they will begin to address counter-argument(s). In many situations a counter-argument reaching a different conclusion is possible. This might use the same data but come to a different conclusion, it may use different data, or it may involve different social or ethical values. Within argumentation lessons it may be the role of the teacher to play ‘devil’s advocate’ by presenting counter-arguments to students and pushing them to explain why they are incorrect.

- Any of the component parts of an argument can be criticised, including the warrant; the link between data and a claim. The critical analysis of claims, data and counter-argument makes use of higher order thinking skills which will really stretch students to engage with the data and scientific knowledge required to interpret it.

- A detailed argument on a complex issue may involve several simple arguments where the intermediate conclusions build up to an overall claim. The strength of the overall argument will depend on the strength of the component parts.

- As the quality and complexity of students arguments increases it is expected that they will be able to support and justify their arguments through making explicit links to relevant and correct subject knowledge.

Adapted from Science in Society (Nuffield Foundation, 2012).

No comments:

Post a Comment